(12) Nike Monument

First half of the 2nd century B.C.E.

Retaining walls composed of basalt fieldstones; building constructed in pebbly calcareous sandstone

Statue constructed of at least eight fitted components carved in Parian marble; base built in Lartian blue-veined marble from Rhodes

(left) Newly restored statue in the Louvre, © 2014 Musée du Louvre / Philippe Fuzeau; (right) View of the Nike Monument from the north, © American Excavations Samothrace

Unquestionably the most famous monument in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods is the Nike of Samothrace. Rising to a preserved height of 5.57 m, the statue, featuring a winged figure of Victory alighting on the prow of a marble warship, exemplifies the movement, gesture, and rich texturing of the finest Hellenistic sculpture. Since being removed to Paris in the late 19th century, the Nike has stood prominently atop the Louvre’s Daru Staircase. In this position, the statue commands a dramatic view not unlike that which she held in antiquity, when she overlooked the entire Sanctuary from the highest point of the Western Hill, set obliquely within a small rectangular niche that was cut into the hillside and protected on three sides by retaining walls. While the dynamism of this location—and the communicative power it imparted to the Nike—has never been in doubt, the architectural structure that originally framed the statue remains one of the least understood buildings in the Sanctuary.

Like the statue itself, the Nike’s architectural setting was first revealed by Charles Champoiseau, the acting vice-consul to Adrianople (modern Edirne) who traveled to Samothrace in 1863, 1879, and 1891 in order to excavate and remove the statue to France. Between those expeditions, an Austrian team led by Alexander Conze conducted additional work in 1875, clearing the foundations of the Nike Monument and drawing the first partial plan and section. The American expedition led by Karl Lehmann, joined by Charles Charbonneaux, returned to the building in 1939, 1950, and 1952, conducting excavations in the hopes of finding additional fragments of the Nike and clarifying the building’s chronology. A partial collapse of the retaining walls around the monument in 1962 led James McCredie to undertake additional investigations in the 1980s in conjunction with restoration, focusing especially on the areas immediately behind the damaged walls. Our renewed efforts to study and publish the monument began in 2013, on the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the statue.

Team members cleaning the foundations of the Nike Monument in 2015, © American Excavations Samothrace

From the beginning, archaeologists working at the site were struck by the poor condition of the Nike Monument, especially in contrast to the nearly pristine statue and base which it housed. In large part, this condition is due to the building’s precarious topographic location and the choice of materials used in its construction. Cut into a steep hillside, the Nike Monument was particularly susceptible to seismic events, and unlike every other structure in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, it was constructed of a highly friable pebbly calcareous sandstone. Such a stone is not only extremely susceptible to damage but is also soft enough to be easily broken up into smaller pieces, leading to extensive spoliation during the Byzantine period for what appears to be an industrial complex on the Intermediate Terrace. The early date of the monument’s excavation, moreover, allowed for more modern damage in the 19th and 20th centuries. The removal of the Nike’s marble socle blocks to the Louvre in 1879 left the ashlar foundations beneath vulnerable to spoliation, and all were gone by the time Lehmann’s team made the first detailed state plan of the monument in the 1950s.

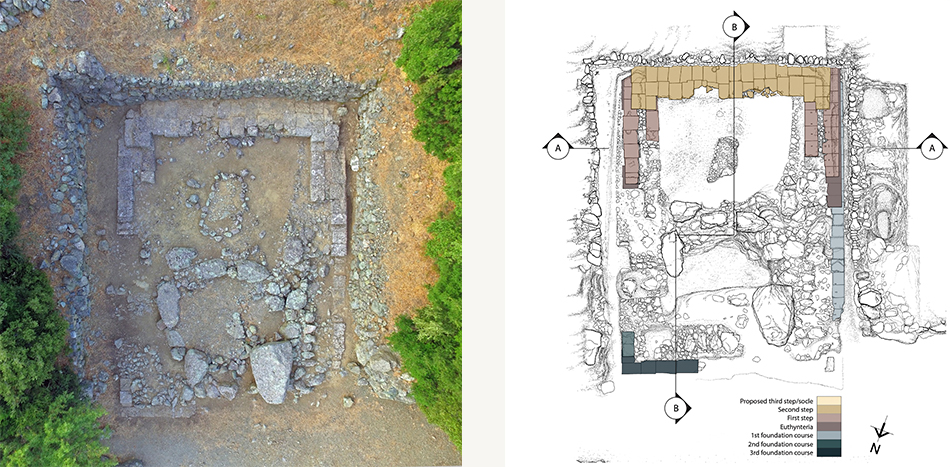

(left) Aerial view of the Nike Monument, © American Excavations Samothrace; (right) Actual state drawing with krepis color-coded according to course, © American Excavations Samothrace

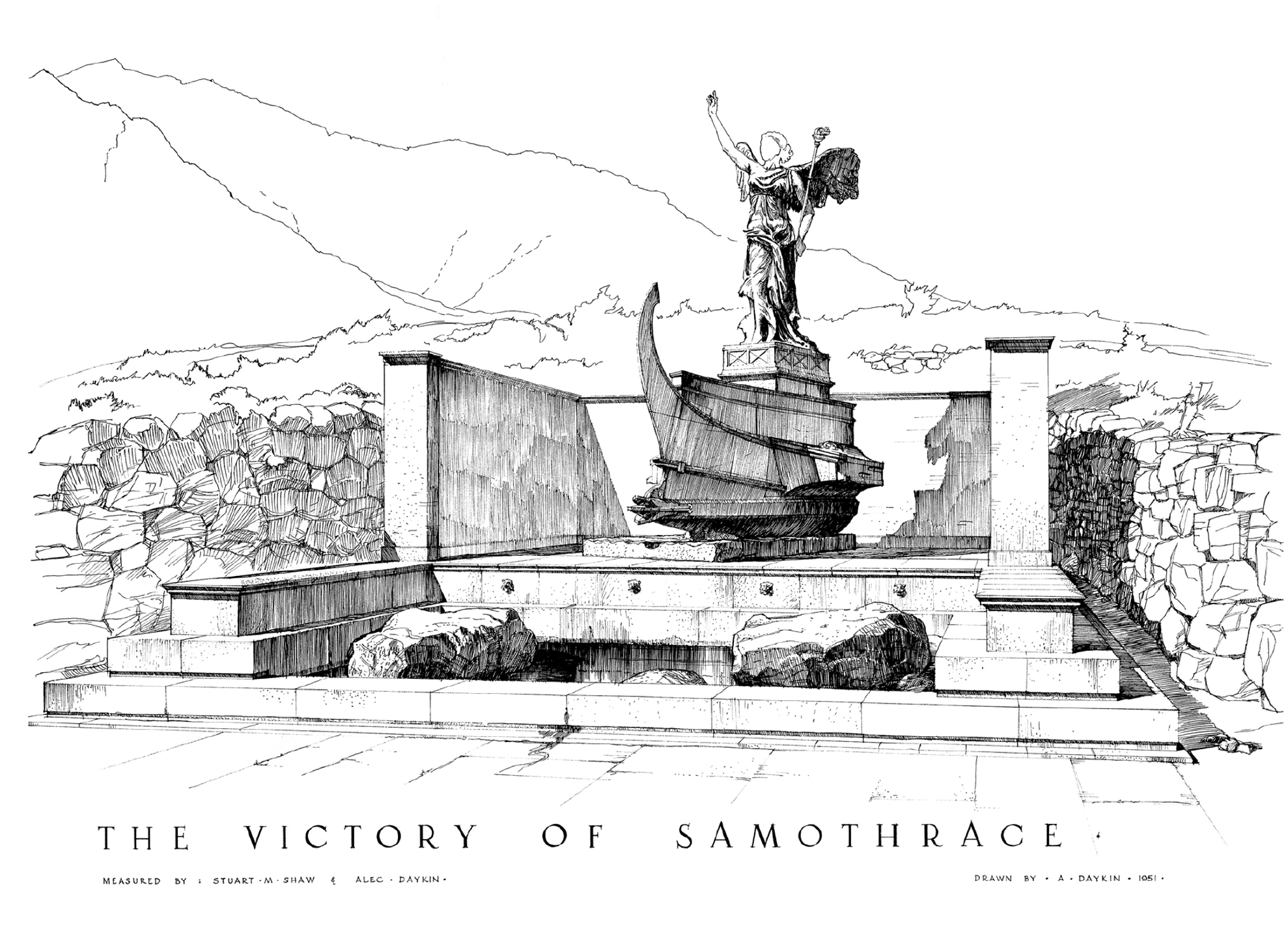

In plan, the Nike Monument consists of a rectangular krepis, ca. 9.50 m wide at the level of the euthynteria and ca 13.40 m in length. While the building’s scale is clear, its poor state of preservation has significantly impacted scholarly attempts to reconstruct it. Champoiseau initially misinterpreted the marble blocks of the Nike’s prow to be an Egyptian-style tomb. All other early reconstructions, meanwhile, have developed around the idea that the building was divided into two chambers by a lateral cross wall. Most influential of these has been the model developed by Karl Lehmann and Alec Daykin, who interpreted the monument as a naturalistic fountain combining landscape, water, and sculpture. Under their reconstruction, the Nike would have stood at the back of a shallow upper basin, triumphantly alighting on the prow of a warship as it sailed through a lower basin’s rocky shoals, formed by three enormous boulders.

Re-examination of the building’s architecture and cataloged finds in recent years has demonstrated the impossibility of this interpretation. The pipes directly behind the monument, for instance, which would have fed Lehmann’s purported fountain, instead directed water to the nearby Stoa, and the boulders of the hypothetical lower basin sit at an elevation that would have been below the building’s original floor level. In place of the fountain interpretation, however, it is now clear that the Nike’s surrounding architecture took the form of either an open peribolos, surrounded by a low wall, or a roofed, prostyle naiskos. While the evidence leans toward a roofed enclosure, there are important caveats that cause us to continue to offer both a roofed and an open reconstruction as we continue to work on the monument. It is even possible that the building took both forms during its lifetime: originally constructed as a covered building but rebuilt as an open space after being damaged in the Roman Imperial period.

3D model reconstructions of the Nike in an open peribolos (left) or a roofed enclosure (right), © American Excavations Samothrace

In addition to helping clarify the Nike Monument’s reconstruction, recent research has allowed us to better understand its decorative program. Each excavation campaign has uncovered large quantities of wall plaster in white, blue, and red, some with drafted edges. The structure’s sandstone walls were entirely covered in plaster and, like many other buildings in the Sanctuary, originally had wall decoration with raised panels and drafted margins. A handful of stone and plaster moldings recovered in the vicinity further indicate the existence of Ionic architectural features, including at least three different articulated horizontal courses. Fragments preserving miniature Doric-style fluting also suggest the presence of an engaged decorative order similar to that of the Hieron. More intriguing still are the remains of large-scale plaster lion’s heads, which include fragments of locks, upper and lower jaws, and an eyeball. In form, these heads resemble a sort that usually formed real or faux waterspouts on the sima course or served as the mouths of wall fountains. Because the surface of the surviving tongue does not show signs of water damage, however, they must have been affixed to the walls in a purely decorative manner.

Plaster components of a large lion’s head, attached to the building, most likely an imitation waterspout, © American Excavations Samothrace

Like the statue which it housed, the chronology of the Nike Monument’s architecture is difficult to determine with confidence, and a recent reanalysis of pottery from within the monument has not yielded material connected with its initial construction. Traditionally, both statue and monument have been dated to the 2nd century B.C.E., but because the architectural frame is larger and deeper than the statue requires, it is possible that the building was originally designed for a different purpose and only later came to house the Nike. While the origins of the monument may be unclear, however, its longer-term history is evident from the nature of later interventions. The building’s position within a niche cut into the hillside would seem to have demanded retaining walls from the beginning, but the basalt boulder walls that frame it on three sides are dated by pottery in their fill to the 2nd century C.E. Additional evidence, moreover, indicates that these walls were constructed following substantial damage to the original architecture. On the south side, for instance, the retaining wall was built directly on top of the building’s surviving krepis, and on all three sides, the walls are chinked with fragments of the monument’s unique calcareous sandstone. Because major parts of the statue of Nike were excavated in excellent condition relative to its surrounding architecture, it thus seems likely that the retaining walls constructed in the 2nd century C.E. were aimed squarely at protecting the statue and allowing it to continue functioning within the Samothracian cult.

Selected Bibliography (Architecture):

- Clinton, K., L. Laugier, A. Stewart, and B. D. Wescoat. 2020. “The Nike of Samothrace: Setting the Record Straight,” AJA 124, pp. 551–573.

- Conze, A., A. Hauser, and O. Benndorf. 1880. Neue archäologische Untersuchungen auf Samothrake. Vienna.

- Hamiaux, M. 2001. “La Victoire de Samothrace. Découverte et restauration,” JSav 1, pp. 152–223.

- Hamiaux, M. 2006. “La Victoire de Samothrace. Construction de la base et reconstitution,” MonPiot 85, pp. 5–60.

- Hamiaux, M. 2007. La Victoire de Samothrace. Paris.

- Hamiaux, M., L. Laugier, and J.-L. Martinez (Eds.). 2014. The Winged Victory of Samothrace: Rediscovering a Masterpiece. Paris.

- Knell, H. 1995. Die Nike von Samothrake. Typus, Form, Bedeutung und Wirkungsgeschichte eines rhodischen Sieges-Anathems im Kabirenheiligtum von Samothrake. Darmstadt.

- La Rocca, E. 2018. La Nike di Samotracia tra Macedoni e Romani. Un riesame del monumento nel quadro dell’assimilazione dei Penati agli dei di Samotracia. ASAtene, Supplemento 1. Athens.

- Lehmann, K. 1998. Samothrace: A Guide to the Excavations and the Museum. 6th ed., rev. J. R. McCredie, Thessaloniki, p. 102.

- Wescoat, B. D. 2020. “Architectural Documentation and Visual Evocation: Choices, Iterations, and Virtual Representation in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrake,” in New Directions and Paradigms for the Study of Greek Architecture, eds. P. Sapirstein and D. Scahill, Leiden, pp. 311–315.