(11a) Stoa

ca. 300-250 B.C.

Dolomitic limestone, basalt, plaster

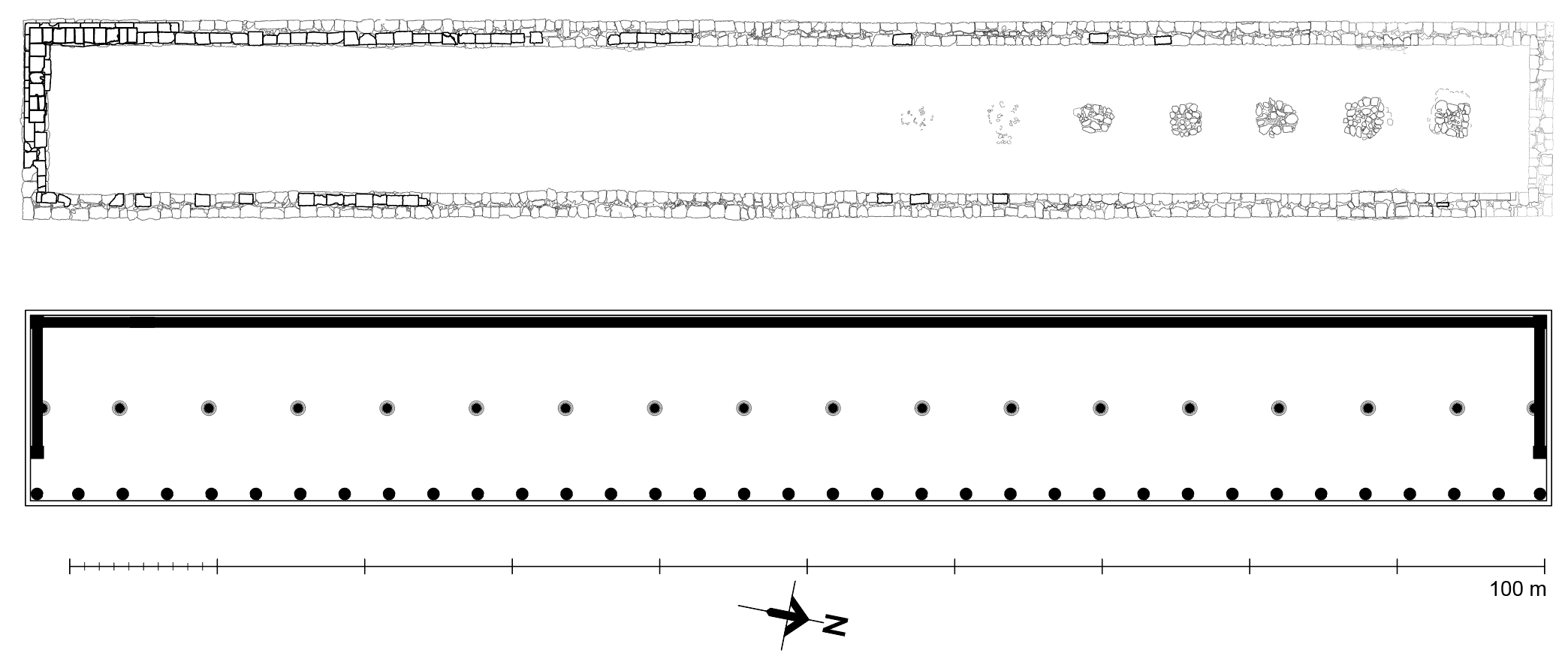

ca. 104 x 13.40 m

The Stoa, which was built along the ridge of the Western Hill in the mid-third century B.C, set a clear western boundary of the sanctuary. Its imposing position offered a panoramic vantage point for visitors to look out over the cult buildings to the east. The long portico functioned in close relationship with the Theater, Nike Monument, and the dining rooms in the western area of the Sanctuary. It sheltered many visitors to the Sanctuary, presumably not only initiates to the mysteries but also those attending the annual festival.

The ruins of the Stoa were first reported in 1866 by the French expedition of G. Deville and E. Coquart. They assumed that the building’s size and elevated position corresponded with its religious significance, and they dubbed it “le temple principal” or “the main temple.” The Austrian excavation of 1875, however, uncovered the foundations of the building and revealed the plan of a stoa rather than a temple. The French-Czech mission of 1923 also focused on documenting the large building. The American excavation led by J. R. McCredie finally revealed the Stoa in its entirety during campaigns between 1962 and 1967.

(a) Austrian excavation of the Stoa, 1875 (b) American excavation of the Stoa, 1962 (c) Emory and NYU students clean the Stoa foundations for surveying and aerial photography, 2017.

The extraordinary length of the Stoa, ca. 104 m from north to south, makes it the largest structure in the Sanctuary and one of the longest stoas in the northeastern Aegean. To accommodate a building of this size on the naturally hilly terrain, an artificial terrace was necessary, created by digging into the hill at the building’s south end and extending the plateau 25 m to the north. Where it is set into the hillside at the south, the building rests on only one course of foundation blocks. At the terraced north end, however, it is supported on seventeen foundation courses, which in total are as tall as the columns of the superstructure. By virtue of its imposing size and position, the Stoa gave monumental architectural definition to the western area of the Sanctuary.

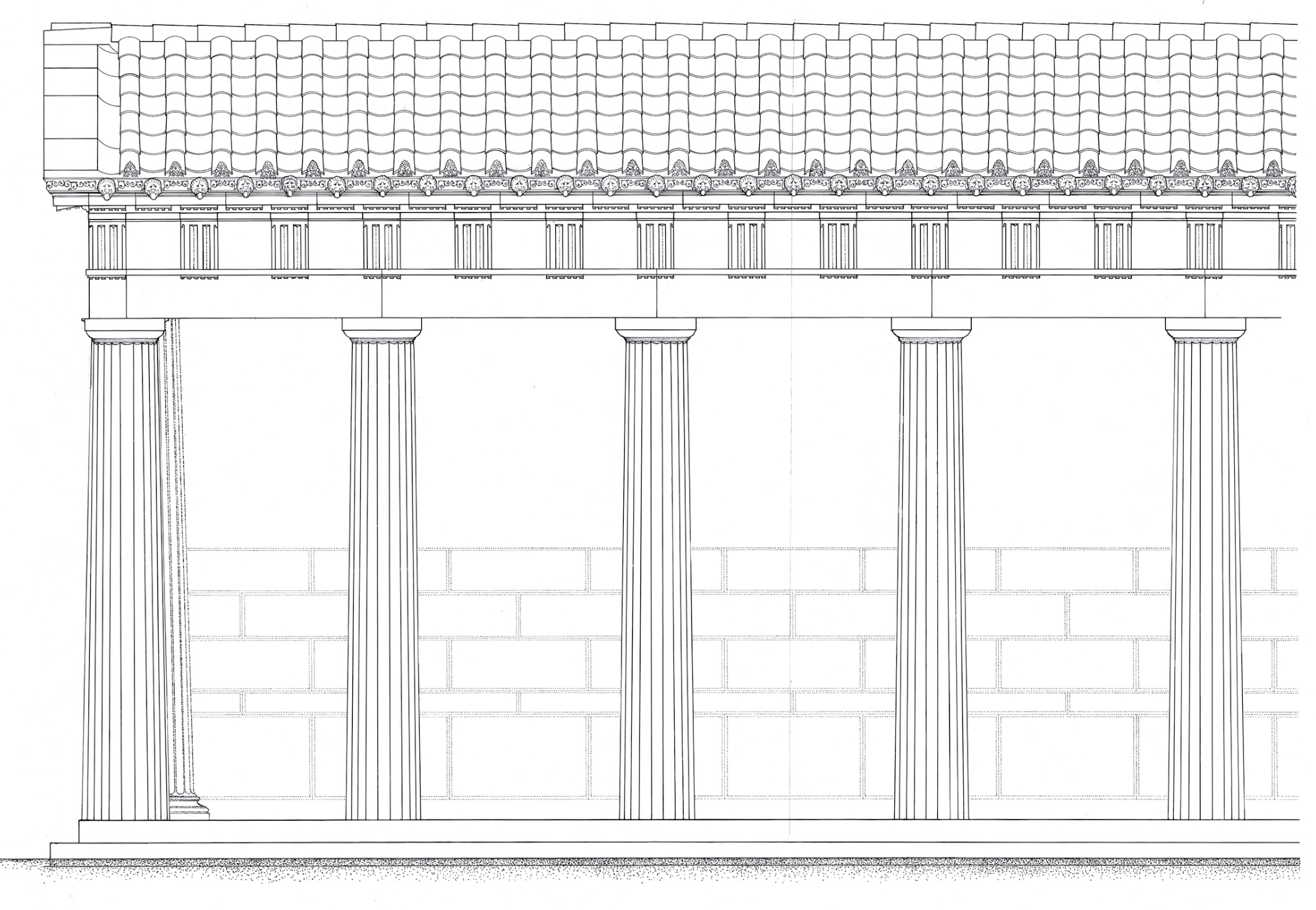

The structure consists of a single long hall facing east, with a Doric prostyle façade of 35 columns. The Doric entablature, with its frieze of triglyphs and metopes, wraps around from the façade to the short sides of the building at the north and south. The long west wall, however, has a streamlined design without the standard elements of a Doric entablature or cornice. To support the roof, there is a central colonnade of 16 Ionic columns running down the middle of the building. The Ionic colonnade terminates with engaged half-columns at the north and south ends.

The Stoa is significant not only for its placement and size but also for certain key features of its design. These include the use of corner pilasters at the exterior corners, engaged Ionic half-columns that complete the internal colonnade, plastered interior walls painted in imitation of drafted margin masonry, and a sima (gutter) of elaborate mold-made tiles with lion head water spouts. Although this limestone building stands out in its material from the Sanctuary’s marble buildings, design features, such as the combination of architectural orders (here Doric and Ionic columns), is in keeping with Samothracian building trends.

The Stoa was built of dolomitic limestone, but was covered in a coating of plaster. On the interior, the plaster was scored, shaped, and painted in imitation of masonry, with projecting white, red, and blue panels. The use of painted plaster in imitation of masonry to articulate the interior is a feature that the Stoa shares with other buildings in the Sanctuary, most notably the Fieldstone Building, the Hieron, and the Neorion (Ship Monument). Many fragments of painted plaster from the interior walls have traces of graffiti. Most of the fragments preserve only a few letters, but we can make out the word or phrase “ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ” or “ΕΠΙ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ”, which means “when so-and-so was basileus.” This is a familiar formula for dating initiate lists, and it appears that the painted plaster walls were used to record lists of names of initiates. It appears that the Stoa terrace was a desirable location for display, where the wealthiest and most powerful initiates set up large monuments, while regular visitors may simply have recorded their presence by scratching their names on the Stoa’s walls.

Selected Bibliography:

- Conze, A., A. Hauser, and O. Benndorff. 1880. Neue archäologische Untersuchungen auf Samothrake. Vienna: Druck und Verlag von Carl Gerold’s Sohn (especially pp. 49-51)

- McCredie, J. R. 1965. “Samotharce: Preliminary Report on the Campaigns of 1962-1964,” Hesperia 34: pp. 100-124. (especially pp. 101-110) 17

- –––. 1968. “Samothrace: Preliminary Report on the Campaigns of 1965-1967,” Hesperia 37: pp. 200-234. (especially pp. 201-204)

- –––. 1979. “Samothrace: Supplementary Investigations, 1968-1977,” Hesperia 48: pp. 1-44. (especially pp. 8-12)